C A N A D I A N H I S T O R Y

•

J O U R N A L

“The Buffalo Jump”

“x10-head-smashed-in-buffalo-jump-and-environs-20120805-16.jpg” by Roland Tanglao is licensed under CC by 2.0.

Chapter one of “The Buffalo Jump” written by James Brink, elaborates on how moving it can be to physically explore a historical site, how easily historical stories such as “The Buffalo Jump” can be perceived differently by others, and why historical events such as this, can be looked at in different perspectives. The author’s writing is centralized around the location of a buffalo jump recognized as a Provincial Historical Resource in Alberta (pg.6), known for its descriptive name, “Head-Smashed-In”. This specific location was once inhabited by Aboriginal People of the Great Plains, and contains evidence showing that it was the site of a mass buffalo killing for the benefit of the Aboriginal Peoples.

Brink discusses an aspect of history that can be hard to understand until you have physically stepped-foot on the same ground where an event occurred so many years ago, and how spiritually moving it can be to have the realization that the place that you’re in at that moment, the purpose of which you are standing there, and the culture of that specific location are entirely different. This statement stood out to me the most because I have experienced that feeling before, and I think that feeling is one of the greatest things about history; how just physically being in an area can create a sense of imagination and wonder as to what it was truly like for those standing there in the past.

Brink’s story of the “Head-Smashed-In” buffalo jump contains information regarding evidence that has been found on the site of excavation at the event location, including buffalo bones and stone tools. However, he also brings up a good point that relates to his quote, “We can never go to the past; hence, we can never truly know it” (pg.6). Although Brink has spent years of his life examining and dedicating his time to the conservation and research of the historical site, he makes the point that even with artifacts such as maps, buffalo bones and stone tools, there is still controversy about whether or not “Head-Smashed-In” is in fact the actual site of the tragic tale that has been a part of the Blackfoot people’s culture for many years. Because the maps do not have precise coordinates, because no one from the time is still living today, and because there are different stories among elders, there may never be a definite correct answer.

Within the chapter, the author mentions the concept that as an individual looking back on this event in present day, it may be hard to envision how a life style such as those of the Aboriginal People of the Great Plains and their buffalo hunts could be enjoyable. The mass buffalo killing at first glance might appear to be a violent, cruel, lazy, or pointless event. However, maybe it only appears that way because the culture that we live in today is so incredibly different from that of those living in that period. If we think about a reasoning for the buffalo jump, and the planning of the buffalo jump, there are a few points mentioned that help the reader to understand a possible reasoning to the event. This includes the purpose of a social gathering, and a critical food supply for the people living in an area of scare food resources. Because it is impossible to go back in time and experience what really happened and why, it is difficult to fully understand why certain things happened in the shape and form that they occurred.

In summary, Brink’s discussion about the feelings that can occur from physically being in a historical location, his elaboration on the truth about how the history of “Head-Smashed-In” buffalo jump has uncertainties, and his points on how the history of the event can be viewed differently by others, the chapter provided me a new perspective on buffalo jumps that occurred in the past, and enlightened me about what studying a historical site may be like.

The “Acadian Identity”

Rock formations at the Bay of Fundy, Canada. J. Watt – Photograph taken 1976, scanned from positive-film slide in 2010.

The Acadians were descendants of French Settlers who made the journey to North America from 1604 onward, creating communities along the shores of The Bay of Fundy, which in present day is known as Nova Scotia, Canada. This particular area of settlement was situated across the land that was considered a main section of the border between New England and New France. In Naomi E. S. Griffiths article, Acadian Identity: The Creation and Re-Creation of Community, she brings up the argument that people do not inherit the identity of the community they live in, it is a phenomenon created and developed by human beings. In this journal entry, I will touch on the key aspects of Acadian Identity, the “Golden Age” of the Acadians, and why the British became anxious about the Acadians and how they acted on it during the 18th Century.

What makes an Acadian, an Acadian? It took me digging deeper into the reading to truly get a grasp on what aspects distinguish the difference between a New France and New Britain settler from an Acadian. The term Acadian began when explores claimed Acadia in 1604, which were communities spread across the demographic area of Canada that we now know as Nova Scotia and claimed this land to be Acadia. These were the first people to journey to the area before the core group of settlers arrived in New France and New Britain later on. A question that came to mind during the beginning of the reading to me was, “Why did these people want to come settle here in the first place?”. But not long into the read, Griffith explains, “Those who migrated to Acadia, were simply seeking improved social and economic conditions for themselves and their children.” The Acadians were not politically stable as they were pulled back and forth between New France and New Britain rule and weren’t controlled by the priests in their political life. Though the Acadians were happy with their lifestyle, the lack of government and the belief that they had ownership of Acadia, later created concern for the more powerful British.

The years of 1713-1755 were known as Acadia’s “Golden Age”. Because Acadia had an informal administrative system, life was quite good for the people who called Acadia home. Due to a lack of war involvement, many Acadian families were able to stay together and continue to grow and develop. Not only were families kept together, few people were dying as there wasn’t any access for epidemics to reach the people, leaving families and children healthy. In 1719, the Fortress Louisburg was also developed, which created room for trade. Food was abundant, and the communities had plenty of farmers, hunters, and fishermen; all which contributed to the growing economy. In addition to healthy families, Acadian’s were able to practice traditional celebrations including songs, dancing, and legends, creating a form of kinship and entertainment. Finally, although Acadia has been ruled under British government in 1713, they did not have a significant involvement in the everyday life of Acadian’s, allowing them to have a strong say in their political life. Unfortunately, this luxury only lasted so long.

Prior to 1755, although signed under oath to give ownership of the land to the British, Acadians were determined that as indigenous people of the land, they would not agree to engaging in war with the French or the Native Indians. Unfortunately, the British eventually realized that the Acadians were set in their ways and did not want to come to an agreement. This determination to remain in some ways different, or unlike the British, caused fear and frustration for the British. Due to amount of resistance from the Acadian people to agree to fight in the war, the British militaries had strong enough power to have the Acadians deported in 1755 and they were either sent to other colonies or refused and were shipped back to Europe.

The Acadian story is not a happy one, and it demonstrates the impact of political power on people’s lives. Those people who came to the Acadia in 1604, and their descendants were not born into a community that shaped who they were. People, such as the Acadians, tried to live an abundant life that suited the families that called Acadia home, in an environment that felt was right to them as a community. However, as easily as they were born into a certain community, they were just as easily removed, and the culture of community that they had grown up in, was destroyed without any choice or say.

1 Griffiths, Naomi. “Acadian Identity: The Creation and Re-creation of Community”. Dalhousie Review 73: 3 (1993): 330

2 Griffiths, Naomi. “Acadian Identity: The Creation and Re-creation of Community”. Dalhousie Review 73: 3 (1993): 329

3 “Timeline.” CBCnews. https://www.cbc.ca/acadian/timeline.html.

Griffiths, Naomi. “Acadian Identity: The Creation and Re-creation of Community”. Dalhousie Review 73: 3 (1993): 331

4 Griffiths, Naomi. “Acadian Identity: The Creation and Re-creation of Community”. Dalhousie Review 73: 3 (1993): 335

5 Griffiths, Naomi. “Acadian Identity: The Creation and Re-creation of Community”. Dalhousie Review 73: 3 (1993): 335

6 “Timeline.” CBCnews. https://www.cbc.ca/acadian/timeline.html

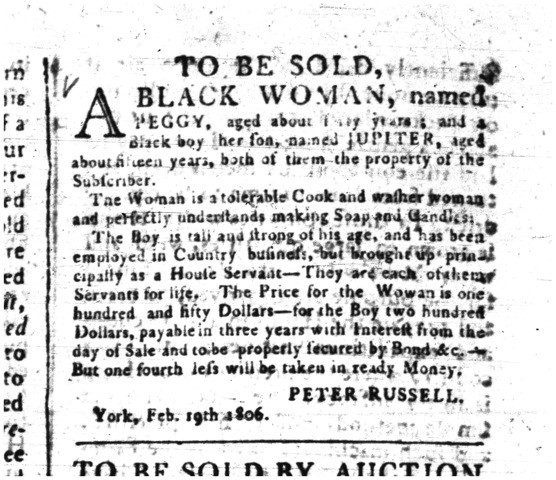

Slavery In Upper Canada

Peter Russell. “TO BE SOLD, A BLACK WOMAN.” From Slavery in Canada? I Never Learned That! (2013) http://activehistory.ca/2013/10/slavery-in-canada-i-never-learned-that/ (accessed October 4, 2018).

While reading Afua Cooper’s, “Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803”, and exploring Ontario’s online exhibit titled, “Enslaved Africans in Upper Canada”, I was able to grasp a deeper understanding of English law around slavery and the stories of four African slaves that lived in Upper Canada. I found theses readings particularly interesting as the document I chose to do my document analysis on for this class, was mentioned on the website and discussed in more depth.

Cooper discusses the status that enslaved Africans held in Upper Canada. He refers to slavery as an “inhuman system in which one group of persons permanently owned the life and labour of another group and had the power of life and death over them”. Not only is the idea a human being considered as property a disturbing concept, but the fact that another human had the legal right to control the life and death of one is sickening. Cooper elaborates on the conditions of enslaved Africans in Upper Canada. This includes the slave system being hereditary, that slaves had little or no social status , and that both French and English slaves were under the full authority of their owner. Slaves were also deprived of all rights including marital, parental, proprietary, and even the right to live. It is hard to believe that this was the reality for enslaved Africans at one point in time, as these terms seem so unjust today.

Sophia Burthen Pooley was one of many enslaved Africans in Upper Canada. She was born a slave as both her parents were also slaves. Though born in the states, Sophia was taken to Niagara at 7 years old. Once she arrived in Canada, she was sold to Mohawk Chieftain, Joseph Brant. Sophia lived in Brant’s Upper Canada home, and was sadly beat and scarred by Brant’s third wife. At 12 years old, Sophia was sold yet again to an English man for the cheap price of $100.00. It is painful to think that the ownership of a human could come as easily as a paid dollar figure.

Another known slave was referred to by the name of Henry Lewis. Henry escaped his owner in Upper Canada and fled to New York in the search of freedom and rights. After his arrival in New York, Henry wrote his previous owner, William Jarvis, a controversial letter.

His letter entailed his wish to purchase himself by paying amounts to the mayor if his current city, as he allows him the freedom he deserves. This showed an act of rebellion on his part by taking the risk of running away, for the desire of fair human rights.

Peggy, who was the subject in my document analysis project, was a slave owned by Peter Russell. As she had children of her own, they were born as slaves and were under the ownership of Peter as well. Peter tried to sell Peggy due to troublesome behaviour, however falsely projected her in a news ad stating she was competent even though he believed otherwise.

Dorinda Baker and her 3 children were owned by Robert Gray, who was Upper Canada’s solicitor general at the time. Robert did something unlike most slave owners, by releasing Dorinda, her children, and her mother from slavery. He did so by writing directions in his will to release them after his death and left them money and property to ensure security. I feel that Gray’s actions were done through a realization of the wrongfulness of slavery, in an era that viewed slave labour a necessary system in agricultural economy.

1 Afua Cooper, “Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803,” Ontario History, Vol.99, Issue 1 (Spring 2007): 7

2 Ibid.

3 Afua Cooper, “Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803,” Ontario History, Vol.99, Issue 1 (Spring 2007): 8

4 Afua Cooper, “Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803,” Ontario History, Vol.99, Issue 1 (Spring 2007): 11

5 “Enslaved Africans in Upper Canada,” Archives of Ontario, http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/slavery/index.aspx.

6 Afua Cooper, “Acts of Resistance: Black Men and Women Engage Slavery in Upper Canada, 1793-1803,” Ontario History, Vol.99, Issue 1 (Spring 2007): 12

Aboriginal Presence During the Gold Rush

“BC-032-Barkerville” by rcbrazier – Brazier Creative is licensed under CC by-nd 2.0.

Mica Jorgenson’s “Into That Country to Work: Aboriginal Economic Activities during Barkerville’s Gold Rush”, and “A Great Humbug” clearly identify that the presence of Indigenous people in the Barkerville gold mining area was misunderstood and not appropriately documented throughout history. “A Great Humbug” which includes primary source documents from individuals that experienced the gold rush first hand, provides some clues to the involvement of Indigenous people with the miners when they arrived in BC for the gold rush. In addition, Jorgenson’s article provides evidence alluding to the fact that Indigenous people were not only present, but also had economic roles during this period.

Jorgenson mentions that historian’s have not yet made the involvement of the First Nations Peoples during the Barkerville goldrush a topic of study. He also states that historians believed that Aboriginal people were “absent from the mines and towns” , and argue that the Aboriginal population of the gold rush area was wiped out by disease before the miners arrived. However, the article later discusses a primary source that includes an interaction between an Indigenous woman and the miners after the epidemic. This interaction proves that disease did not entirely wipe out the Aboriginal peoples in the surrounding areas. Jorgenson also provides information regarding reports that suggest the Dakelh people occupied the Barkerville region before the gold rush even occurred. This supports the fact that Indigenous people were on the land before and continued to be on the land during the gold rush in Barkerville.

Through analytical literature, Jorgenson reveals that the Aboriginal peoples hunted, fished, gathered, farmed, raised their children, and exchanged their labour in different combinations, and as opportunities presented themselves” , all of which possibly contributed to the development and economy of Barkerville. Another example of Aboriginal presence during the gold rush is provided within a primary source extracted from “A Great Humbug”. The source is written by a miner by the name of Charles Major who writes in a letter, “The Indians are not very troublesome at the mines”, giving reality to the belief that Indigenous people were a part of the gold rush, even if that meant there were few of them.

It is within these sources such as letters and reports, that hold the truth about the presence and role of Indigenous people prior to, and during, the gold rush in British Columbia. The lack of study around Aboriginal involvement at Barkerville and its surrounding areas has unfortunately not provided the Aboriginal peoples with the credit in the gold rush aspect of Canadian history that they deserve.

1 Mica Jorgenson. “Into that Country to Work: Aboriginal Economic Activities in Barkerville’s Gold Rush”, BC Studies, no.185, 2015, 111

2 Ibid 112

3 Ibid 111

4 Charles Major. “News from British Columbia”, The Daily Globe, January 2, 1860